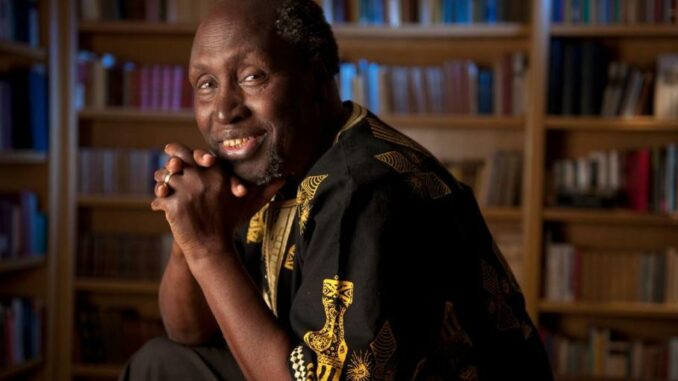

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who has died on May 28 aged 87, leaves behind a literary legacy forged in defiance and devotion—an unyielding voice that chronicled Kenya’s journey from colonial subjugation to sovereign statehood.

His narratives, echoing the anguish and aspirations of a continent, broke through bars of imprisonment and the silence of exile, each line a testimony of endurance. For six decades, his pen danced between worlds—English and Kikuyu, past and future—mapping the scars of history and the dreams of liberation. While the Nobel Prize eluded him, he became something far more enduring: the conscience of African literature.

Born in colonial-era Kenya as James Thiong’o Ngũgĩ, he emerged from the crucible of colonial violence, shaped by the trauma of displacement and the death of his brother during the Mau Mau uprising. His literary star rose quickly, blessed by the mentorship of Chinua Achebe and fuelled by the political fire of independence. Yet it was in 1977, the year he renounced English and adopted Kikuyu as his literary weapon, that Ngũgĩ transformed from novelist to revolutionary. His fearless critique of post-independence leadership earned him imprisonment and forced exile, yet even from a maximum-security cell, he birthed his Kikuyu novel Devil on the Cross on prison toilet paper—a symbol of resilience against repression.

Ngũgĩ’s later years saw him rise as an academic titan and a global champion of linguistic decolonisation. He tirelessly argued that African languages held the soul of African thought, often sparking fierce debates—even at the cost of his friendship with Achebe. Personal controversies and health struggles marked his twilight years, yet none could dim the brilliance of his craft or the clarity of his conviction. As his physical voice fades, the echo of his work endures—bold, unrepentant, and revolutionary. The world mourns not just a man, but a movement—a mind that reminded Africa to write, speak, and dream in its own tongue.